Well, did he or didn’t he? Did Coronado and his army pass this way 480 years ago on their explorations of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas?

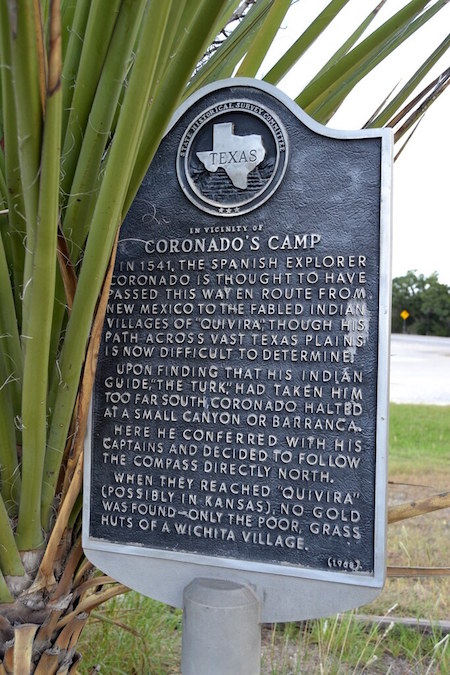

This State Historical Marker (photo) lies some 12 miles west of Abilene where U.S. 277 and FM 89 cross. The locale goes by the name Coronado’s Camp. The marker proclaims that Spanish explorer Coronado “is thought to have passed this way.” He was en route from New Mexico to the fabled Indian villages of “Quivira.”

This State Historical Marker (photo) lies some 12 miles west of Abilene where U.S. 277 and FM 89 cross. The locale goes by the name Coronado’s Camp. The marker proclaims that Spanish explorer Coronado “is thought to have passed this way.” He was en route from New Mexico to the fabled Indian villages of “Quivira.”

And yes, that possibility exists. And if it is true, then this location is of great historical significance. It marks what likely was the first appearance of Europeans in this part of the world.

But herein lies the mystery. Coronado’s route across the Southwest and the Great Plains remains murky and enigmatic. And subject to various conjectures and theories. Yet that uncertainty also accounts for much of its appeal.

If the route were clearcut and established, the geographical aspects would be settled. But the passion for answers, or even just for active speculation, would be quenched. And with it so would much of the debate.

It’s the debating part that so many historians love.

This marker was erected in 1968. Since then, research and archeology have unearthed some clues to Coronado’s route. This research does nothing to help the Taylor County claims to its share of the Coronado legend. But then the research is not sufficient to completely extinguish the Taylor County claims, either.

Let’s back up and fill in with some historical context.

In 1541, a brief 50 years after Columbus’ discovery of the New World, Spaniards plunged deep into the Great Plains. And they claimed for Spain the midsection of what is now America.

The party departed from Tiguex, an Indian settlement on the Rio Grande River just north of present-day Albuquerque. From there, Coronado marched east into what is now the Texas panhandle.

According to earlier interpretations of his peregrinations, his path drifted southeasterly. The route allegedly took him to the point now known as Coronado’s Camp. It was at Coronado’s Camp that Coronado purportedly decided his Indian guide had steered him wrong. And it was here that he changed course and embarked on a direct northerly route.

That’s how the early versions have it.

Consider now this more recent interpretation, divulged in a 1996 newspaper article by Peter Sprotts:

“A long, thin line of troops snaked through the buffalo grass atop never-ending mesas. Their leader’s dreams of conquest and the fabled seven golden cities of Cibola were fading before the reality of adobe pueblos, carved-wooden kachinas, and clay pots. Under a hot May sun and the command of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, the hundreds of Spanish soldiers, servants, and pack animals on the expedition wearily put one foot in front of another, likely hoping for respite.

“If Donald Blakeslee, an archaeologist with Wichita State University in Kansas is correct, he has pinpointed the place where the Army’s hopes [for respite] were realized—at least for two weeks. Sifting through the soil of Blanco Canyon, just east of Lubbock, Texas, Dr. Blakeslee and a team of researchers have discovered a concentration of copper cross-bow-bolt points and other artifacts that likely came from Coronado’s conquistadors.”

If Blakeslee was correct, then Coronado’s path stayed more easterly, rather than southeasterly. The route would not have taken him as far south in Texas as present-day Taylor County. See accompanying map for the revised version of Coronado’s route.

But who really knows?

Coronado’s own records, and those of his contemporaries, are notoriously problematical. The entire party hardly felt they knew where they were going. And the idea of being lost was never far from their minds.

So is it possible that Coronado did not alter his course northward at Blanco Canyon [or maybe never even arrived at Blanco Canyon]? And is it possible he instead plunged down to what we call Coronado’s Camp? And that he there elected to change course and head north? Who can say he didn’t? His descriptions of landmarks were so sketchy or non-existent that his route remains, to this day, hotly debated.

So for our part, we’ll stick with Coronado’s Camp (it does fit some of the descriptions Coronado gave for his stopping/turning point) And we’ll wait for more conclusive research to come along before we give up on our local landmark.

As long as the Texas Historical Society hasn’t given up on it, we haven’t either.